A conversation about the life’s work of Laura Stone, grandmaster

When I arrive at The Studio in idyllic Deventer, the stately home with the name of a law firm in the entry way takes me aback for a moment. Until Laura Stone opens the door and embodies tranquility as she appears.

By Connie Witte

Published in Taijiquan en Qigong Tijdschrift 24, decembre 2018

Temporarily anyway, because in the living room, next to the comfortable armchairs, she immediately takes the lead: ‘Have you seen them?’ and points to a room-high wall hanging on the opposite side of the room. Against a warm soft red background, the embroidery shows eight figures in vivid colours; the eight immortals from Daoist mythology.

Temporarily anyway, because in the living room, next to the comfortable armchairs, she immediately takes the lead: ‘Have you seen them?’ and points to a room-high wall hanging on the opposite side of the room. Against a warm soft red background, the embroidery shows eight figures in vivid colours; the eight immortals from Daoist mythology.

Laura: The wall hanging was embroidered at the end of the 19th century and brought from China to Indiana, USA, close to my home in the early 80s. Paying for something like that, it wasn’t cheap! But it made such an impression on me that I took on the responsibility of ownership. It’s all because of T’ai Chi, that I was so touched by Chinese culture.

You became involved with T’ai Chi at a young age?

I was 20 when I started, but had seen it for the first time three years before, from a student of Grandmaster T. T. Liang. When I was seventeen I went to Amherst, Massachusetts, to the Graduate School of Education, an alternative, experimental school; I was allowed to attend classes along side the graduate students. A photography and yoga teacher showed me T’ai Chi one day. That made such an impression: it’s been almost 50 years, but I remember it exactly, I even know what I was wearing. He also showed me a book about T’ai Chi, maybe that of GM T. T. Liang.

Then I went to a small Liberal Arts College and conservatory where I practiced yoga because there was no T’ai Chi. At that time I saw Judyth Weaver do the form of Professor Cheng Man-Ching, but that was far away from where I lived. I was searching; at such a young age I wanted to be more calm. I’m from Chicago and life there is busy and competitive, people talk loud and fast. I didn’t feel connected to my body either, and definitely didn’t want to be asked to dance.I didn’t do that. I wasn’t really athletic either, but I was active, and in team sports at school I was a bit aggressive, always at the front. T’ai Chi was really good for me; it gave me not only physical, but also mental peace.

On July 4, 1972, I saw an older man under a tree along Lake Michigan doing T’ai Chi. I never saw him again, but Robert Cheng, his teacher, became my first teacher.

You were visually touched by T’ai Chi?

When I saw it, I knew immediately it was for me. I went to him three or five times a week, and although he also did a form of T’ai Chi Sanshou, I didn’t realize it was a form of self-defense. For me it was a kind of dance; I was touched by the interaction, by the beautiful movements.

When I went to Indiana University to study music, I was looking for someone to continue to train T’ai Chi; 35,000 students but no one who taught T’ai Chi. At the Free University, you could offer classes or make requests for classes. I filled out a card: ‘I’m looking for people with whom I can practice T’ai Chi’. Two weeks later my name was on a poster, as a teacher of T’ai Chi, and soon after that I was in a conference room with 20 people. Four of the attendees wanted to learn T’ai Chi from me. Of course I asked my teacher, because, although intensively practicing, I had only been training for 15 months: ‘May I teach T’ai Chi’, and he said: ‘If you are honest about what you know and what you don’t know’.

Quickly starting to teach can be a boost for your own learning process?

I am a precise person and I’ll never forget that first year: now I can start a movement at any moment of the form, in the middle of a movement as well, but not then. My teacher said, “You think too much.” I couldn’t do anything else, it was my first year.

At that time I met the man I was going to travel with; his first T’ai Chi teacher was Grandmaster William C. C. Chen. My roommate in Bloomington said that his piano teacher was going to give her debut at Carnegie Hall, did I want to go to New York with him? So yes, 14 hours of driving, no problem! It turned out to be great timing, because when I visited Professor Cheng Man Ching’s school, Shr Jung, the professor had just been dead for about six months. His dedicated senior students were there: Maggie Newman, Ed Young, Lou Kleinsmith, Tam Gibbs, maybe also Mort Raphaël, Stanley Israel, really the inner circle, were still together there. I was allowed to push hands with them. Great.

I also went to the GM Chen’s school. He was practicing a push hands exercise with the students called “bread dough”, where you push directly on the body of your partner to move with it and to soften up. GM Chen was pushing on the belly of a pregnant woman. So beautiful. So relaxing and enjoyable. Fine training and atmosphere.

You were visually affected again?

This is interesting; you connect it to the visual but it is what I feel at that moment, something happens to me kinesthetically. I’m not that good at connecting to T’ai Chi with images. It’s more like seeing how it feels and imitating that; I can easily imitate movements. I like some images, like the waves of the ocean, with the sound and how that water goes up and down, but when you start talking about mechanical things, no.

The slow, gentle and friendly movements of T’ai Chi Chuan are like the waves of the ocean. They roll on and flow again, producing an uninterrupted flow of energy.

Grandmaster William C. C. Chen

GM Chen is known for his body mechanics?

That’s right, he always emphasizes relaxing and letting go. Also how you can uproot someone else with effortless power. Like the waves of the ocean, those waves are not trying to swell up! Just relax and at a certain moment you can feel the energy rising; that was what attracted me. Those first years we trained a lot at his classes and workshops. Hands on. GM Chen trained personally with everyone.

Images touch you?

Only later. In 1976 I went to Hawaii; my friend Peter Kneip studied calligraphy with Ho Tit-wah, who had just painted 100 works. When we met, I told him how I felt about every painting. It was magical, that sense of visual art; I came from music!

In 1977, I went back to Hawaii with Peter and did calligraphy twice a week with Ho Tit-wah. That was great; I had studied music and had been doing T’ai Chi Ch’uan for five years, I was already teaching; at that moment the two arts came together for me. It was, and still is, the experience of how you hold the brush, how the tip of it touches the paper, the interaction with the ink, the paper, the pressure, the concentration and the meaning. Years ago in Amsterdam I gave a workshop on single whip, expressing the movement like calligraphy.

Her arms paint the movements in the air.

Ho Tit-wah wanted me to continue my calligraphy training. But I couldn’t do everything, so I continued with T’ai Chi Ch’uan and music and meditation. But calligraphy keeps coming back in to my life. That was the case in 1990 with Cong Zhi-yuan; he taught at my T’ai Chi Ch’uan school in Bloomington: Chinese painting, calligraphy and Pakua.

Now there is Wang Ning, a Chinese man who has lived in Frankfurt for almost 30 years. I met him at the annual International Pushing Hands Meeting in Hanover; it’s amazing how he connects T’ai Chi with calligraphy. I invited him, in March to give a workshop here in Deventer.

In Hawaii I also studied four to six hours a day for six months with a teacher who was half Chinese half Hawaiian, Sam Kekina, an old surfer and boxing champion. In that half year with him I learned 12 forms. He liked to tease me with self-defense manoeuvres and that kind of woke me up.

At that time, 1977, Peter and I also followed a week-long workshop with Grandmaster Benjamin Lo. We didn’t know who he was! There I had my first experiences with sword, with holding postures and pushing hands. Benjamin Lo was a very warm and playful person.

After that I went to Taiwan for three months; I studied sword with Mr. Tuan You-chang. When you study sword you understand, this is a martial art! He was a warm, friendly teacher, Buddhist, and a bit heavy, but when he jumped it was as if he was flying, so beautiful.

At that time I was already quite frustrated with pushing hands with GM Benjamin Lo: he touched you and BAM, you were slammed against the wall. And now what? What should I do? Relax, yes, relax.

But with Grandmaster Chen everything was OK: he gives you suggestions, images, hands-on things, it was fun and he’s still like that, I think he’s such a special person. He says: ‘right, right, right’. Then you relax. Then he gives a refinement to be able to improve and understand the movement.

On my way back from Asia at the end of 1978, I visited him in New York. He said: ‘You don’t have that much money, come back later. Just watch the (beginners) class. That was interesting; no pressure to participate. I was completely sold. In June ’79 I visited him again and said: ‘I would like to take every class that is appropriate for me’. He asked: ‘Do you want to box?’ ‘Yes’, I said.

You were a pianist! But you wanted to box?

No, not really. I was a good girl and had never been a fighter, but he offered it, so I did it. Well, that changed my life. Boxing does something to you. Now back to body mechanics: so you have the softness and agility of pushing hands and uprooting, because he started with uprooting, and making sure you’re comfortable with intimate contact, and being playful. It was very active then, with many drills. I immediately invited him to my school in Bloomington, Indiana, and that was the beginning of something extraordinary.

Beginning in November 1979, Grandmaster Chen came to Bloomington two to four times a year and in between I went to him. That was very intensive and special. In 1981 people started coming from outside my own school. There was a core group that trained intensively with him in my school. I organised about 50 workshops with him. In ’82 or ’83, I was 30, I went to Hawaii as an assistant and asked him if I could name my school in his lineage: A Center for William C. C. Chen’s T’ai Chi Ch’uan. I received my diploma from him in 1986 and in 1991 he named me Master in a workshop. Both came as a surprise, by the way. At that time my T’ai Chi career really took off.

Grandmaster Chen has been coming to the Netherlands since 1978?

Yes, and in ’87 I came with him to Europe, to Cornelia Grüber in Switzerland, to Amsterdam where Maartje van Staalduijnen was active, and to Bremen, the school of Luis Molera.

Yes, and in ’87 I came with him to Europe, to Cornelia Grüber in Switzerland, to Amsterdam where Maartje van Staalduijnen was active, and to Bremen, the school of Luis Molera.

After that I went to Sweden for two years before Grandmaster Chen went there, to the school of Claes Tarras Ericsson; to the school of Luis Molera in Bremen and to Linda Lehrhaupt in Bedburg, near Düsseldorf. Starting in 1988 I gave workshops every year in Europe.

What has kept you here?

Love has kept me here. I met Fred van Welsem at a workshop. After we trained with GM Chen in New York together at Christmas time 1993, we spent two weeks on holiday in my house in the woods around Bloomington where we decided to get married. It took me a year to close my school and say goodbye to my students. From then on, I wanted to live a more integrated life, not only focused on my career. I taught T’ai Chi and started playing piano again. That is another common thread in my life, which I have picked up here again, the piano. We were looking for a place to start a new life, and that became Deventer.

What do your workshops consist of?

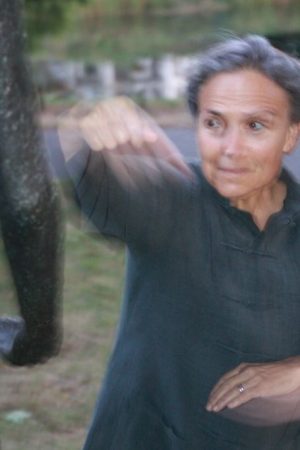

What I do first is the body mechanics, applying the principles in the form, applications, push hands, and finally in boxing. I love boxing and enjoy teaching it. For me boxing is directly connected to the T’ai Chi form, principles and philosophy, and it’s delightfully active!

What I do first is the body mechanics, applying the principles in the form, applications, push hands, and finally in boxing. I love boxing and enjoy teaching it. For me boxing is directly connected to the T’ai Chi form, principles and philosophy, and it’s delightfully active!

Everything from the internal feeling. I let people first touch themselves in a relaxed way. Then the next step of touching a partner is almost self-evident. Practicing together in an enjoyable way, which means: in an environment that is safe. I pay attention to everyone and see what it takes to do the exercise properly, and allow the space in which it is okay to try it out.

Push hands can very quickly become competitive, too hard; especially women get scared. I do push hands focusing on soft contact. The exercises I use are from GM Chen with influences from Dr. Tao Ping-Siang and GM Peter Ralston, so soft and effortless. I go very slowly and take a small piece of the interaction to practice, to try to overcome the reluctance, and to show that it is possible to connect. That is a conviction of mine: people want contact, we are social beings. But how exactly can you give permission, or better, space so that it’s okay?

Your husband, you said, became a lawyer mediator. Is fighting in the same relationship to T’ai Chi boxing and push hands? Or is being soft just meant to find an opening for an attack?

I’d like to go into this in more detail. Because for five years now, I have consciously known how that soft contact and boxing are connected.

When you feel attacked, you tend to fall back on your automatic reaction, which comes from your reptilian brain. I first heard about this from GM Peter Ralston; when you experience something aggressive, the reptilian brain reacts automatically. With T’ai Chi you can build a kind of foundation of softness and trust, of space and flexibility. It is also based on balance and harmony, when everything is connected and you are in your relaxed power. But you use your power in a conscious way, you know what you are doing. That effortless power comes from softness, from doing almost nothing. That is one of the most important things in T’ai Chi Ch’uan. For me, that soft, playful contact builds up that foundation. So we’re busy training something that’s not normal.

Let me go back for a minute: T’ai Chi Ch’uan is a defensive art. Your first reaction is always to connect, to go with (follow), to ensure your safety, and not to go against the force with force. You then have a moment, a fraction of a second sometimes, to see what is needed. There are powerful movements, maybe you need them, maybe not. So you train to create time and space. Make contact, so you’re also not running away. Also a reaction of the reptilian brain, if something scares you, you resist/fight of run away/flee. So make contact, physically, maybe also eye contact, you are fully present, you often let someone come very close, while keeping your own space, that’s what we train.

In boxing you also train the other way around, you see what happens when you give a punch or take a punch, there is more excitement generated from speed and power. How can you stay relaxed under pressure?

You are the aggressor?

I would say the attacker. And in doing so, you choose whether to let your force or aggression be felt, there’s a big difference. It may be that someone attacks you, not out of aggression, but out of a desire to survive.

In boxing, you first learn the technique in the style of GM Chen.

Hold up your hand, and as quick as lightening, she punches my hand with her fist a couple of times.

I touch you fully but without penetration. Our automatic reaction is to press into your hand, but we don’t, we train “end positions”, so called memory shapes, which are positions of soft connectedness in structure. You then meet the resistance of the other person, his or her solidity. And I’m not going to let go, I’m going to meet it and I’m not going through it. In English we say “I stand my ground”. At the moment of contact there is space and connection in my own body everywhere, and I connect with earth and heaven.

That is the same as in PH, that I connect with your roots, with your whole body. My image for a good push is that of a parent who throws his or her child in the air and softly and solidly catches the child. My ideal push feels good and totally connected. In the PH-game you stay in contact and go along with your partner, often meaning that you don’t do anything for a long time. Until THE moment comes. I’m not someone who does very dramatic things, like the flowing, powerful uprooting of GM Peter Ralston or the soft joint locks of Dr. Tao Ping-Siang. If Dr. Tao only had a piece of your finger, you would know that if you moved even a millimetre, it would hurt a lot. You didn’t feel anything, only that it was completely locked, so beautiful. Recently I did a workshop with Tony Ward in Hannover and saw that staying in that softness is really possible. I realize that I don’t have such a training, but I do have very good basics and a continual feeling of spaciousness. You have to make a commitment to that softness, if you don’t, your reptilian brain will always play up. It is a lifeline.

It seems dangerous to me to silence the reptilian brain?

Of course there are limits, in a life-threatening situation you have to have that reaction. You have to be aware of your reaction; in the end everything happens in a split second. In T’ai Chi there is a saying ‘from nothing to something’, your intention is connected to ‘something’, there is nothing in between. To take a moment to relax, to ground, to have your intention clear, and then to take action is too slow: you are too late. So you stay in nothingness, in the open space, grounded and trained; if something happens, the action is there immediately.

You go along softly, there is contact, and in both boxing and PH the right timing is important, perceiving very precisely. GM Peter Ralston also says: you are open, you are connected, you are in interaction. At normal speed you don’t have time to think, you see what is happening, you perceive, you feel the whole, your eyes are open but not too focused, and you move with the interaction.

What GM Chen does in the beginning, and I’m very grateful for that, is: no blocking, so no warding off. Because if you are continually blocking, you are constantly protecting yourself. You continually go on, back and forth, like a beautiful game.

We also play with strength. I have an exercise in which we take punches, on the belly and the jaw, from very soft to hard, just like in music, a crescendo. You learn to receive properly, and to funnel it to the ground, you go to your limit, but not over it. Then you say: This was enough. Because when you play beyond your edge, you fight, run away or freeze. We stay just before that: how much more can you take? Then you know that. The other way around, it’s also an exercise for the person who gives the punches. He can say, I don’t want to go any harder, so he knows where his limit is. You experience how much that is by observing and experiencing very precisely. You learn to give punches with power but without aggression.

It seems difficult to me to punch a classmate, whom you don’t have anything against. Do you only discover your edges by crossing them?

We touch the edges. Then you can choose whether you want to cross it or not. Expanding your boundaries, that’s what happens in class. Of course only people come to train who want to investigate their edges.

And now we are talking about the physical side of T’ai Chi but it also works in relationships for example, how do you deal with situations at work or in a conflict? That you are there and take your place fully, you don’t have to be hard, but you are sure, grounded, present, open, and you listen. We haven’t used that word yet, it’s very important to listen.

Someone recently told me: listen to the whisper of your body, so that it doesn’t have to shout…

Most people don’t listen very well. That’s what T’ai Chi does, it will make you aware of inner noise, distraction, for example. A beginner has no room to do anything other than learn those movements. But when you’re done with that, you have peace and clarity. The noise is gone. Listening yes, that is what I try to achieve in my lessons.

For me it’s all about softness; I tell my students, this is what you can get from me. This is what I have to offer, softer than soft, I am one of the softest. Only then will the reptilian brain come to rest. By training hardness you stimulate that brain.

About five to six years ago, when I was 60, I felt a very deep acceptance, acceptance, of where I was with T’ai Chi. Until then it was ‘there’s always room for improvement’, ‘one day I’ll get it all figured out’. But then I said ‘Okay, done, I don’t have to prove anything’. Wanting to prove is in my character, and working hard, being a good student. But I thought, hey, this is another part of my life. I’ve taught and studied T’ai Chi all my life and for the first time there was complete acceptance. Coincidentally also then my student Alwin Wubben started making movies of me in my lessons. When I saw them I was satisfied for the first time in my life. At the age of 65, I decided to start a one-time three-year intensive training to pass on what I know. Last year, the first year, there were 17 participants, now 10.

And in the meantime, haven’t you been recognised as Grandmaster by Grandmaster William C. C. Chen?

Yes, that’s special too. I’ve always kept going to Grandmaster Chen. In January I was at a workshop in Bremen with three students. On Sunday morning, just between classes, Grandmaster Chen said: ‘Well, Laura has been here with me the longest’ (other people have been there with him for a long time, but not since 1979), ‘I think it’s time to call her Grandmaster, she’s doing it so long and she has so many students, actually you can call her Big Sister’. For him, the title Grandmaster is a kind of generational title; if you have your diploma you are a master, then you have a level at which you can pass something on. And if you train masters, you’re a grandmaster. There was a lot of confusion about it, for example one of my colleagues said that you’re not my grandmaster. I said, no, of course not, that’s not the intention, because we are colleagues. So Big Sister is a good alternative. It is, however, a great honour and a great responsibility in the whole of the lineage, in the line. Of course it’s not just any old thing, I don’t know anyone who has received this title from him.

How does this title fit your desire to accept your level?

Maybe that’s the hallmark of grand-mastery. When you get a title like that, you already are that, it’s the recognition of it; it’s not that you’re going to have to become one now.

Aren’t you afraid that you need to maintain a top level?

No, that’s not what it’s about. We can talk about my fall earlier this year, or the fact that someone at class pushed me away, or that someone got in a good punch. Grand-mastership doesn’t mean that things like this will never happen again; I’m still a teacher.

Many teachers are afraid of giving pushing hands or boxing classes; they don’t want to be shown up. But that happens. The question is: what do you do with it? In Indianapolis I wanted to demonstrate an application of the first Ward-off as a pull with a student who was this big guy. Normally he loved the lessons and he was a real fan, but then, in a large group with many beginners, he wanted to challenge me and decided to really root. I couldn’t demonstrate that particular technique. That’s an interesting moment, so what do you do? I just pushed him the other way. That’s grand-mastery, that you go along with what’s happening. Another might say that as a grandmaster you should always be able to perform the technique you want, but that’s not how I see it.

I call myself a T’ai Chi athlete. That’s the name I came up with when I fell earlier this year. Immediately after the fall and later during my recovery I used a lot of T’ai Chi. A very precise body awareness that has helped me enormously with this. Another nice word I came up with was movement intelligence.

Why T’ai Chi athlete?

I don’t look like an athlete, but I do have that awareness. I’m a T’ai Chi athlete, not in competition, that’s not my thing, but in precision, in how you can control your body.

People have told me that they expect a completely different image of me than what I am, my physical appearance.

Your fame and name raise a different expectation.

I can also punch really hard. GM Chen said when we started boxing: ‘You have to learn how to take it’. If you know that you can take hard punches, you have a lot of self-confidence. So my friends and I trained hard twice a week for the first few years and hitting each other as hard as possible.

I can also punch really hard. GM Chen said when we started boxing: ‘You have to learn how to take it’. If you know that you can take hard punches, you have a lot of self-confidence. So my friends and I trained hard twice a week for the first few years and hitting each other as hard as possible.

I loved that, and still do, rough-housing like boys. And without blocking, then you’re not busy with defending yourself and you can see what’s happening. Now I do: how do you go with the attack first and come back? But at that time my macho side wanted to be hit in my face as hard as possible: come on, no problem. That trait has positive and less positive sides; I can’t make myself smaller. Of course I have a soft side that sometimes wants to be taken care of, but when it comes down to it I hold my ground. Learning to move neutralise and join the movement of another in T’ai Chi has been my salvation.

A conservatory study also requires a strong will?

Yes, and a strong will stands in the way of softness. My first Zen teacher told me that it is necessary to have a goal, to have a vision of how you can become a pianist or a T’ai Chi-er. But if you use too much willpower, you get in your own way. Everyone knows that.

So he called it the ‘allowing will’; you have a will, personal strength, but you don’t over use it. When are you working too hard, when is your will working against you? When there is too much physical tension. With T’ai Chi you have effortless power. You need strength, it’s not just softness.

Yes, I am so happy with what I do, I am a teacher, that’s what I have been my whole life, even as a little girl, when we played. I am glad that I have come to this point, this is what I have, I can pass it on. And people have ideas on how to develop further; one student is a physical therapist and takes it with him in his professional life, another is with the police, and so on. What are they going to do with it, that’s what I find so interesting. It is said that the really good teacher wants his students to transcend him. That is difficult, because the teacher always wants to be the teacher. This great mastery is not only about your skill but maybe about your wisdom. I really hope they surpass me in all kinds of ways.

It makes Laura emotional.

I’m also still growing in my practice. I certainly feel that, but in a completely different way: Not to having to prove myself, or that there is always room for improvement.

Ambition?

I have a lot of ambitions, that’s what I had with my school, I’ve always worked hard and still do, but I also have a lot of energy. In the early 70’s one of the first teachers of the time, GM Chung Liang Al Huang, a Chinese dancer, had lights on his body. I still have that on my bucket list, to do the form, and then be filmed, so you don’t see my body, but only the lights in the darkness.

What makes you a good T’ai Chi teacher, that you are good at T’ai Chi or that you love people?

T’ai Chi suits me very well; somehow I easily learned the form before. But learning form is one thing, the internal work, that’s another. When I had been practicing GM Chen’s style for six months, I said: I’ll stop with all those forms. What has remained is the interaction. I think that’s T’ai Chi Chuan’s greatest gift. You can do the form very nicely, but it’s only in contact, in interaction, that you really learn what you’re doing. In interaction you learn to deal with other situations, with other people. That’s what makes T’ai Chi so different from yoga; yoga also creates a beautiful body awareness, absolutely. It has helped me a lot and still does. And I also like Aikido, but T’ai Chi Chuan is much more intimate, you are always in contact with someone else: how do you relax in contact with someone else? A lot of people are afraid of that, they have trouble diving into contact. They come to T’ai Chi because it is not interactive, because of the beautiful form, the meditative side, for health.

But it’s self-defense, without applications you don’t develop a sense of what the individual movements mean. For example, I never say ‘hold the ball’ because for me that movement to this side is an elbow thrust or up to the other side to make defend yourself. I see all those movements in the air, the strokes, like calligraphy.

As she talks, her arms and hands are constantly circling through the air.

And nothing is fixed, I don’t use that word either. I used to use the terms floating techniques or soft uprooting. And pushing hands is actually ‘no hands’, your hands only express what is happening in your feet and your body. In boxing I consciously use my hands strategically, because I don’t want you to see past my hands, I want to distract you. GM Chen has a name for it, he calls it palm dancing.

You call T’ai Chi “music for your body”

But in my classes, I never use music; the form has its own rhythm.

And then for some minutes it’s completely still while she’s doing part of the form from her armchair.

One of the most beautiful moments in my life was when I gave a demonstration of T’ai Chi on a cliff in Hawaii with the ocean under my feet. Every end of a movement (posture) is the crest of a wave. The pauses in breathing literally nourish your cells. When you are under stress, your body has difficulty getting nourished; literally, at the level of the metabolism of your cells. If you are habitually tense, this form, as well as other forms from the Cheng Man-Ching’s lineage and qigong, helps you because there is more breathing out than in, leading to softness, to relaxation.

You also do dance improvisation?

Not so much at the moment. But I have music, timbre, composition, T’ai Chi in my body. And combining that with images, because I have started to look much more actively since practicing Chinese calligraphy. When composing I always used my voice, I played classical piano. Recently, my voice came up out of meditation, out of trust and open space, letting it sound and at the same time listening. And from there I have felt, constantly unfolding and growing, that I came more in contact with Life Energy, if I can put it that way, which is much larger, Cosmic Energy.

And of course this is also possible with T’ai Chi: that you are not there, you are in the exercise, in the energy. It comes through you, between heaven and earth. I call it T’ai Chi dance improvisation.

This morning I woke up with a word: ephemera . It must be because everything you do, the improvisations with your voice, with piano, with your body in dance or T’ai Chi, is not fixed, it only exists at the moment. Except your calligraphy.

But look at that calligraphy, a really good piece of calligraphy is not fixed, it moves!

I have said so much about me, my T’ai Chi life. That could not have happened without all the special teachers, pupils and the love that inspire me and give me life energy. I feel so much gratitude.

On a day of her intensive training that I was allowed to attend, I see the same mixture of softness and power that I experienced during our conversation; flawless precision and passionate interventions in a very well-structured class. I still hear her saying in the in-between-moments, ‘Nothing’s happening’ (‘niets aan de hand’).

I would like to have so many more lives’, she says when I see her again at the STN Festival. The immortals of the embroidery have ended up in the right place.

Quotes interspersed in the article:

- Music and T’ai Chi Chuan came together for me in calligraphy.

- Learning from Grandmaster Chen is enjoyable; he says ‘right, right’ and you relax.

- You have to make a commitment to softness, gentleness, otherwise your reptilian brain will continue to take over…

- This is what I have to offer, softer than soft, I am one of the softest.

- Learning to go with an attack in T’ai Chi has been my salvation.

- Interaction is the greatest gift of T’ai Chi Ch’uan.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator and editing by Laura Stone.